Medical School Impacts Couple in Professional and Private Lives

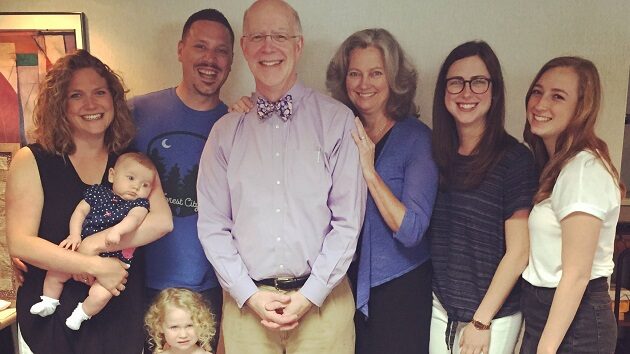

It all started on Orientation Day at Albany Medical College when they shared an elevator. Little did they know that morning that they would end up sharing their lives. From that day forward, Kathleen Kelly, MD ’82, and Arnold Rosen, MD ’82, were inseparable, and two years after graduating, they were married.

“We went through the medical school process side by side and grew ever closer,” said Arnie.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t reflect on my medical school experience. I am the physician I am today because of Albany Medical College,” explained Kathy, who was the Chief Medical Officer of the Swedish American Health System for ten years and is now Assistant Dean of Graduate Medical Education and Designated Institutional Officer at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Rockford (UICOM-R).

“The education I received was a superior foundation for my career,” agreed Arnie, who retired in 2017 after serving the Rockford community as a private practice gastroenterologist for 27 years, and teaching at UICOM-R where he remains on faculty. “Albany Med was the one and only academic center for a very wide region. The spectrum of interesting patients and disease was extraordinary. Kathy and I felt very well prepared to start our internships.” Dr. Rosen serves on the Alumni Association board.

Kathy, grew up in Oneonta, New York, and became acquainted with Albany Med when she took a position as a research assistant after graduating from the University at Albany. Her employer was Herbert Jacobson, PhD, who continues to work at the College and is one of the pioneers of breast cancer receptor research.

Arnie’s route to Albany came by way of his hometown of Pittsfield, Mass., then to undergraduate study at Washington University in St. Louis and back to the northeast.

After graduating, Kathy and Arnie were off to Seattle and Washington, DC, for medical training before settling in Rockford, where they balanced rewarding medical careers with raising three daughters.

The two have given back generously to the college and received the Exemplary Alumni Support Award in 2022.

“We owe so much to the education we received in Albany. We need to express that gratitude by giving back,” said Kathy.

“Albany Med gave me my life – and my wife!” added Arnie. “I can’t thank them enough.”

Meet Matthew Waxman, MD ’02, DTM&H

Excerpt from “Migrant Healthcare in a World with Bustling Borders”

Matthew Waxman, MD ’02, DTM&H

Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Attending Physician Olive View UCLA Department of Emergency Medicine

Dr. Waxman is an emergency medicine physician in California. He has traveled the world caring for migrants and shared his experiences for a feature in the Winter 23-24 Alumni Bulletin.

From early on in my career, I have been focused on global health. I have worked with medics taking care of migrant populations on the Thai Myanmar border. In 2012, I worked on the Ebola pandemic in Sierra Leone as a medical officer in an Ebola treatment center. In 2017, I worked under the World Health Organization (WHO) for a non-governmental organization (NGO) at a trauma stabilization point in northern Iraq caring for casualties during the battle of Mosul. My day job is as an academic emergency medicine physician at a Los Angeles County Hospital.

In the past few years, I have gotten involved with Refugee Health Alliance (RHA), an NGO that provides psychosocial, medical, and maternal child health care to migrants in Tijuana, Mexico. Most recently, RHA expanded to offer services where they are most needed in Reynosa, Mexico, on the Texas border about 1,600 miles east of Tijuana. I started just before the pandemic, coming down for Saturday outreach where we see many newly arrived migrants who are congregated at shelters in outlaying parts of the city. After joining the board of directors, my work now mainly involves reviewing treatment protocols, assisting with fundraising, assisting with grants, and mentoring clinicians in Tijuana and Reynosa.

In Tijuana, Refugee Health Alliance has an established clinical space along the Tijuana River which is very close to the border crossing. The clinical space provides clean water, showers, psychosocial, medical, and maternal fetal health care within the regulations and laws of Mexico.

What did your work involve, from a medical standpoint?

From a medical standpoint, there is an established clinical space close to the border in Tijuana where patients are seen during the week. On Saturdays, volunteers travel to shelters in an outreach to provide medical and psychological support to newly arrived migrants. Saturdays may include trained providers, refilling hormones for trans patients living in an LGBTQ shelter, visiting an outdoor encampment, and always visiting a large indoor shelter. These shelters are often on the outskirts of Tijuana without paved roads and are difficult to access. Saturday shelter outreach is my favorite part of working with RHA as a volunteer. It is a mix of coordinators, students, Mexican medical students and residents, psychologists, and volunteers. At the end of a very busy day, we meet for tacos and beer in Tijuana.

The model of RHA is not to depend on North American volunteers but to have local Mexican, Central American, and Haitian members run the day-to-day operation on the ground. I still very much enjoy working clinically under the license of my Mexican colleagues providing health care to migrants in an austere setting. As a professor of Emergency Medicine, I work closely with medical students and residents and have had the opportunity to share my experience working with migrants.

The migrant population is surprisingly diverse and made up of Haitians, Africans, and people from the Middle East. At the beginning of the Ukraine war, Ukrainian refugees arrived in Tijuana and were prioritized over other migrant groups that had been waiting years for humanitarian parole under the complex asylum process.

It is not uncommon to see migrants who have acquired tropical diseases from walking through the jungle in the Darien Gap between Panama and Colombia.

What surprised you and what would people find most surprising about your experience?

What has surprised me the most is the diversity and resilience of the migrant population. Migrants have come to the southern U.S. border from Haiti, Africa, South America, and the Middle East. The stories of persecution and economic insecurity abound in the migrant population. Many are fleeing the economic collapse in Venezuela and Haiti. Mexicans are seen fleeing the drug war in Michoacan. Others are fleeing persecution as LGBTQ in central America. What they have in common is a desire for a better life for themselves and their children.

As part of the process of helping migrants seek asylum in the United States, I write letters for migrants who have acute medical conditions that cannot be treated in Mexico. As part of the remain in Mexico policy, asylum seekers must wait on the other side of the border for their asylum claim to be reviewed. Often, patients have complex medical problems, and RHA along with volunteer immigration lawyers write letters detailing the patient’s condition to the port of entry asking for humanitarian parole so care can be sought in the United States.

Bearing witness to a humanitarian catastrophe on the border and sharing this experience is part of the work. I was recently in Reynosa, Mexico, where more than 20,000 asylum seekers from Haiti were camped on the Rio Grande River waiting for asylum. These patients were camped outdoors amidst a war between two rival drug cartels just a few hundred feet from the United States. The need for tents, psychosocial and medical care was overwhelming, and RHA has an established clinic and outreach program in Reynosa.

As to be expected, migrants camping outside or in shelters create conditions for infectious diseases, most commonly fevers, upper respiratory infections, and diarrhea in pediatric patients. In adults with chronic diseases, such as diabetes or hypertension, patients may have been off their medications for months as they migrate north. Migrants are the target of violence on their journey north and bear the psychological scars. It is not uncommon to meet children at a shelter visit who have witnessed a parent murdered and fled violence in their home country. These patients have tremendous psychosocial needs, and RHA employs a staff of Mexican social workers and psychologists in the clinic.